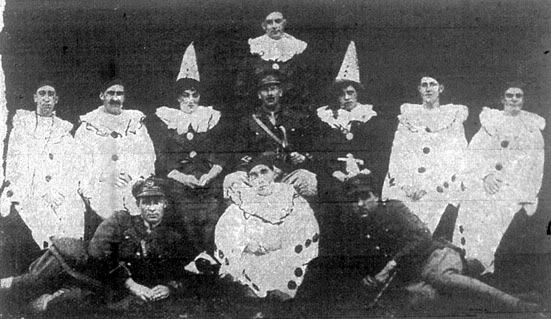

"The Cobblers" performing Aladdin at Tournai. (Photo published on March 1st, 1919) They are all memberst of the 7th Northamptonshire Battalion except those where it is indicated otherwise. From left to right. Standing: Emperor: Private Parkings, Abanazar: Dr. Felton, Vizier: Sergeant Dr. Kelby, Policeman: Lance Corporal Bayley (13th Batt., Middlesex Regt.), Ni-cee (maid to princess): Sergeant-Major F. Hitch, Prince Peko: Private Redmond (9th Batt. Royal Sussex Regt.), Wishee Washee: Private Potter, Widow Twankey: Second Lieutenant F. Judge. Sitting: Princess Balronbadour: Private Hutson, Aladdin: Lance Corporal Pickering (13th Batt. Middlesex Regt.), Santa Luna, Slave of the lamp: Lance Corporal Wright

In 1936, by the time he was promoting "Mutiny on the Bounty", an interviewer asked Charles Laughton what made possible that, having been working in hostelry until barely seven years before, he could have turned into a succesful actor, and, not only that, to have become in that short span of time one of the most respected and sought-for actors in the world at the time.

Laughton's answer was it was a matter of chance, and cryptically added "It took a World War and an act of God" to make him an actor.

Adding a bit of explanation, explained that the "act of God" was his younger brother Tom: "he decided to go into hotel bussiness one day, so I said 'here, take this, I`m going to the stage". Tom Laughton's own version is more detailed, and tells us that Charles didn't enjoy his responsability as hotel manager, a responsability that had befallen him due to the fact that he was the first-born of the family. As opposed to that, he utterly enjoyed every minute of his spare time devoted to amateur theatricals in Scarborough. Charles' family didn't approve his theatrical enthusiasm, and wanted him to keep his mind only in hostelry. Then came Tom to intercede for his parents' cause. Thinking that he had a winning argument, Tom told Charles that he was lucky being the eldest, for he, as the second son, had no chances of inheriting the family hotel and had had to make a living in something else. Tom's strategy failed, as Charles happily seized the occasion to offer Tom his place on the family bussiness, and left to become an actor.

But what about the war? He just says, without much further explanation, that "The war shook me into considering acting as a life work", and one is left pondering: what did he exactly mean by that? One wonders if, having been told cautionary and disencouraging tales by his family about the precariousness of an actor's work (i.e. as opposed to the safer living of hotel bussiness), Charles found that there were ways of life far more precarious and uncomfortable than a thespian's, verbi gratia, that of the soldiers fighting a war. One also considers, on the other hand, if war had on him a similar effect it had on another another Great War veteran, the American painter Horace Pippin, who would declare about his own war experience that "The war brought out all of the art in me, I came home with all of it in my mind, and I paint from it today" (1)

A further clue, however is given by Laughton himself, who, discussing very briefly his time as a soldier, went on to single one experience of which he evidently held a fond memoir : "I saw Leslie Henson play in a pantomime in Lille- it was 'Aladdin'. He was damned funny as usual" . In fact, he would recall in a 1933 interview that "the performance kept alive my latent ambition (to become an actor)". Maybe this was it: the realization that, no matter the bitter experiences, or the glum surroundings, the theatre had the powerful effect of lifting one's spirit. So possibly Laughton reached the same conclusion than the eponimous character played by Joel McCrea in Preston Sturges' masterful film Sullivan's Travels".

But Leslie Henson wasn't the only one performing Aladdin in France around this time. It was also performed by "The Cobblers" a troupe formed by soldiers of the 7th Battalion of the Northamptonshire Regiment... which was the unit where Charles served in France.

But before talking further about "The Cobblers", we might as welll give a smattering about entertainment in World War One.

How the British soldiers were entertained (1914-1918)

Early in the war, the military authorities realized the potential of entertainment for the troops: for the young men in training at home, it offered a more wholesome alternative to spend their spare time than other less reputable ones like alcohol, gambling or prostitution. For soldiers at the fighting fronts, it was also a temporary respite from the harsh realities of trench warfare. For those convalescing from wounds, it was a welcome balm.

The provision of entertainment was often due to the initiative of relevant individuals: many famous actors and actresses of the day would put a show for the benefit of troops, tour in training camps, or in certain cases, even in the vicinity of the front lines, which they would do with the acquiescence of the military commanders. Such were the cases of Lena Ashwell , Gladys Cooper , Harry Lauder, Frank Benson or George Robey , to give just a few names.

On the other hand, there were profesional and amateur performers who were serving in the forces. Among the professionals, we have cases like Leslie Henson, who formed a touring troupe called The Gaieties, or Basil Dean, who would efficiently organize theatres and shows for the Army canteens. Dean and Henson would be the men behind the creation, in the following war, of ENSA, an organization which pertained to the forces, and provided the servicemen with entertainment. However, those serving in ENSA during Second World War worked exclusively as entertainers, whereas those profesional and amateur entertainers in khaki during First World War were'nt usually spared from their regular duties as soldiers (2): those working in a show might be excused from some military routines while preparing a spectacle, but not from returning to their duties once the curtain was down. The casualties at the front meant that the formation of these troupes could be quite variable. Because of this, there was a great empathy among performers and spectators: they knew what made them tick, and a bit of irreverence for humour's sake was tolerated, which provided an extra relief as well.

One of the almost mandatory and usual formations were the Divisional troupes: owing to the large number of men available in a Division (3), there was a good staple of talent to choose from. While the output of these troupes could be variable in quality , depending of the unit, it was usually a well appreciated relief. Commanders were keen on encouraging these performances, and giving some help to make the stagings possible, but the shows weren't officially sponsored, and this was even truer in smaller units (like Battalions). Thus, more often than not the troupes didn't have proper stages to perform in, or costumes... But, quite undaunted by that, they would creatively work to improvise them, quite often with very remarkable results.

There were no girls in the army, so "some of the boys showed how attractively they could be made up as girls". Two female impersonators of "The Cobblers", on the Left, Sergeant-Major F. Hitch, on the right, Private D. Hutson, or "Ida, the Cobblers' Girl", as he was alternatively known.

Since no there were no women in the army at the time, some of these performers in uniform would transform themselves into lovely ladies, not unlike the female impersonators of the Elizabethan theatre, or the Onnagata in the Kabuki Theatre. The best among these female impersonators would be quite sought after to perform, and could be real stars among their comrades.

The Cobblers

The Cobblers, with some Battalion officers (Circa 1916?). From left to right. Lieutenant A.F.T. Bullock, Sergeant Hunting, Captain H. Grierson, Lieutenant Durrant Swan, Lieutenant-Colonel Edgar Mobbs, Second Lieutenant Murray, Sergeant Wenn, Private Driver. Front Row Lieutenant Wharton, Corporal Chapman and Lieutenant Debenham.

Why was that troupe named "The Cobblers"? The 7th Battalion of the Northamptonshire Regiment was one of the Kitchener formations of the early war period. This Battalion was mostly formed by citizens from Northampton, a city known for its shoemaker industry, hence the nickname "The Cobblers" .

According to the available reference, the troupe was first formed in 1916. The battalion had already suffered grievous losses during the Battle of Loos in the previous year. Edgard Mobbs, the international Rugby player who had a relevant role in the recruitment of the Battalion (and who was by then commanding it) encouraged its formation, and even contributed to the programme of the Concert Parties. This early formation of the Troupe would entertain the Battalion and its visitors up to the Battle of the Somme, where the 7th Norhamptonshires would again suffer many casualties.

Lacking other information, we jump to February 1919, a few months after the armistice, when we met a new formation of The Cobblers performing "Aladdin" in Tournai to the benefit of the children of Belgian Soldiers (The soldiers not only entertained the kids but also fed them, with money provided by the Battalion's canteen funds)

It is not unlikely that the choice of the pantomime was due to the fact that Leslie Henson's Gaieties troupe had sucessfully performed "Aladdin" at the reconstructed Lille Theatre earlier in the winter of 1918-1919. It is to be wondered if Henson lent any costumes to the 7th Northamptonshires, even though by what is written about the performance, it seems that the men created imaginatively their own costumes with what they had at hand.

None of the members appearing in the 1916 formation of The Cobblers can be seen in the 1919 photograph. In fact, there are members from other battalions of the 73rd Brigade (to which the 7th Northamptonshires belonged) among the members of the cast... This illustrates quite well the many changes undergone by the battalion due to casualties since the creation of the troupe.

And where was Charles? Well, we certainly don't see him among the members of the cast appearing in the photograph, even though the accompanying article states that those appearing are only part of the cast... Being the stagestruck kid he was, I'd say that it is not unlikely that Charles was very eager to help, and I wonder if he didn't assist the troupe as a chorus boy, as part of a stage horse (or camel?), or a stage hand. At any rate he must have been, without a doubt, a very keen spectator.

This performance by "The Cobblers" must have been one of the last activities of the Battalion with Charles still there. The article covering the "Aladdin" performance was eventually reported in the Northampton Independent in March 1st, 1919, and Laughton had been demobilized in February 14th 1919. It can be said that the effort in benefit of those Belgian children certainly wasn't lost on Charles: a few years later, he and his fellow amateur performers from Scarborough would also perform to aid the League of Help, an association which gathered donations to help with the reconstruction of devastated French and Belgian towns and villages.

Notes

(1) Incidentally, Laughton would have some of Pippin's work in his art collection, prompted by his friend the collector Albert C. Barnes

(2) Cases like Leslie Henson or Basil Dean were, at the time, more the exception than the rule.

(3) Infantry Divisions had an establishment of up to 20.000 men (at full capacity: this number, of course, could vary due to casualties, etc.)

Thanks, ackowledgements and sources

The information and documentation about the Cobblers was kindly supplied to me by Ms. Kate Wills, who is a dedicated researcher on the subject of First World War and Entertainment. Apart from Mrs. Wills information, and old news pages from the Northampton Independent provided by her, This post's sources include an interview to Laughton by Patrick Murphy published in segments at The Sunday Express from November to December, 1933; A 1936 interview with Laughton appearing in Picturegoer's Weekly Supplement; Elsa Lanchester's 1938 book Charles Laughton And I; Tom Laughton's Pavilions By The Sea; L. J. Collins's comprehensive Theatre at War 1914-18 and David Woodall's "The Mobbs Own. The 7th Battalion, The Northamptonshire Regiment. 1914-1918"

Some links of interest

:: Charles Laughton's known First World War experiences at the Huntingdonshire Cyclists website, plus a little update on the matter in this 'ere blog.

:: You might also be interested in checking Horace Pippin's memoirs.

:: A good link on First World War entertainment, at the comprehensive site Great War and Different.

6 comments:

As always, meticulous research coupled with considerable psychological insight. When I think about Charles's role in "The Vessel of Wrath" and particularly the ending, in which he's a pubkeeper/mein host not unlike the role he would have played in the family hotel, I wonder if the entire film isn't some kind of backwards joke--for Charles really ended up the reverse of that film--a primal force in the jungles of Hollywood.

This was fascinating in of itself, but also as a picture of a generation of performers who were forever changed by the War--I think many don't know that Charles, or for that matter, Herbert Marshall and Basil Rathbone served in WWI. Thank you, as always, for this.

Hi Galileosdaughter, pleased to read you again ;D

Good point on "Vessel of Wrath"! Heh, Yes, Charles was a Ginger Ted of sorts in California, not an outcast, but certainly not fitting in any limited "circle" there: Charles' friendships were rather transversal.

There is a similar irony with "Ruggles of Red Gap", where Charles ends as a Bistro Proprietor (no wonder it was Laughton's mother favourite film!), even though Ruggles' own path reflects somehow Charles actual experience, as the butler evolves from serfhood to being his own man.

Yes, the fact that Charles, and a number of other actors (I could add Ronald Colman and Cedric Hardwicke to that list, though of course there were more) is a relatively unknown fact to the general public: those men served as anonymous, unprivileged young men in the war, and the public is more aware of those who served in uniforms (though mostly as entertainers, and certainly with certain privileges owed to their stardom status) in WW2.

In fact, what started me on researching Charles' WW1 experience was the fact that a younger actor who served in WW2 (though never in a frontline, and basically in ENSA) dissed Charles and other WW1 veteran actors because, you know, they were not in uniform in WW2.

Of course, the fact that in WW2 the older actors were beyond conscription age, contributing (as the younger man did) as entertainers, but the younger man didn't ever (as they had done in WW1) fight in any battle... Which should settle the argument quite definitely in favour of the older guys.

Of course, I'll keep younger man's name anonymous, even though seasoned Laughtonians will know who am I talking about. (so please don't mention the name in further comments ;p)

Cheers for discovering me the figure of the Cobblers, it's awesomeee

Ah Charles Laughton, el señor Laughton, since I've seen him as Sir Humphrey Pengallan in The Jamaica Inn,with my Beloved Maureen O'Hara directed my another of the greatest, Sir ALfred, I was shock by his acting...

"Oh Lord, we pray Thee, not that wrecks should happen, but that if they do happen, Thou wilt guide them to the coast of Cornwall for the benefit of the poor inhabitants"(XIX Century ancient pray)

Haya Salud amiga

Gloria, no me defiendo lo más mínimo en inglés, con lo que poco te puedo decir sobre lo que veo escrito.

Sí he de manifestarte mi sorpresa y alegría al encontrar a una conocedora tan entusiasta de la obra de este maravilloso cineasta.

Me congratulo por haber conseguido atraer tu lectura.

Un abrazo.

Saludos Chela,

Laughton está tremendo (y tremendamente divertido) como Pengallan. Con Hitchcock, Laughton tuvo sus choques durante la película, ya que además de actuar, producía la película, y a Don Alfredo era de los que les gustaba controlar el 100% de una película.

Si te gusta Maureen O'Hara (que a quien no, caramba, a quien no), te recomiendo una visita a esta página web, y, por supuesto te recomiendo el visionado de las otras dos películas en las que Laughton y Maureen aparecen juntos: "Esmeralda la zíngara" (Hunchback of Notre Dame, 1939 y This Land is Mine (1943) ambas grandiosas películas en las que los dos están fantásticos (siempre tuvieron muy buena química en pantalla) y que además están editadas en DVD.

Por cierto ¿Sabes que si me he aficionado a las IPAs es por "culpa" de Laughton? Es que un día ví una cerveza en la que ponía "Brewed in North Yorkshire" y me dije que algo que era del condado donde Laughton nació no podía ser malo: fué mi primera IPA y me he enamorado de ese estilo.

Pero Raúl, ¿Cómo no ibas a atraer mi lectura si This Land Is Mine es mi película favorita? ;D

El gusto es mío por leer tu relato inspirado en la película, y es que además clavas la personalidad de Albert Lory.

Respecto al lenguaje, la verdad es que la gran mayoría de los posts están en inglés, más que nada porque con la mayoría de Laughtonianos que conozco me manejo en esta lengua, pero si algún artículo le interesa me lo comenta y ya lo iré traduciendo al castellano.

Post a Comment