Those of you who have seen Muhomatsu no issho (The Rickshaw man, 1958) may remember the scene in the summer festival. Matsugoro (Toshiro Mifune), the humble rickshaw man, volunteers to play the big drums (taiko). He seizes the drumsticks, as if to summon the God of Thunder himself, and starts beating. The audience is awed, carried away by the rythm... an old man rises, barely believing his ears: "that's the rythm of Gion... why, I thought there wasn't anybody who knew how to play it anymore!"

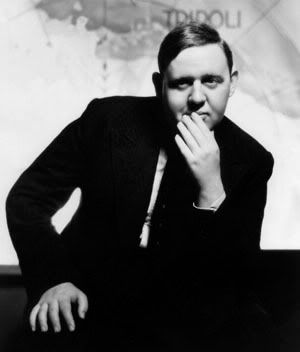

Well, when you watch Charles Laughton's work, it's like hearing again a long-forgotten rythm, like tasting once more a flavour you considered lost. He was unique in his acting. Through it he reached summits where nobody has dared to set a foot again. And the remarkable thing is, he did it against all odds: he didn't have stage parentage, he didn't have the looks, he was a late starter and, in less tolerant times, he wasn't straight to boot.

You have probably come across reductive views of his work: "he's Flamboyant", "he's a ham". Quite often these definitions are thrown by people who just follow what someone else said before: they replicate foreign opinions without daring to put them in question and see by themselves... Now, look with your own eyes and you'll find an actor who offers substance, imagination, subtleness. An actor who makes characters come alive. An actor engaging you and making you reflect. An actor considering his art as a means to teach you.

We can only try to imagine how was his work in the theatre, as Brecht put it, what an actor does on a stage is such "fleeting work". J.B. Priestley clinged to the belief that somewhere in a fourth dimension, theatre performances are still there, and wished time-travels were possible to enjoy memorable performances again. Then he wrote "Film needs no time travelling. Here on the screen - looking rather odd and old fashioned perhaps - is exactly what you wrote, what the actors performed, years ago".

Luckily for Laughton, he didn't despise the medium (sound film was then in its infancy), and was as committed to his film work as much as he was to the stage. So through the cellulloid time machine we can travel back in time, to the thirties, and watch Nero, Dr. Moreau, the clerk in "If I Had A Million", Henry VIII, papa Barrett, Ruggles, Inspector Javert, captain William Bligh, Rembrandt, surviving snippets of emperor Claudius, and, topping the decade, Quasimodo... You can follow forward into the forties and, never mind what you've have been told: you'll find that his performances in "This Land Is Mine", "The Suspect", "The Big Clock" and "The Bribe" are worth the ride. As you enter the fifties the time machine falters as studios seem to ostracise him and he's mostly seen in episodic roles and concentrating his energies on the stage, however, "The Night of The Hunter" suddenly flashes: you can't see him, but you feel he's there. Reaching the end, among his four last appearances he brings forth three unquestionable hits: Sir Wilfrid Robarts, Gracchus, Seab Cooley... and this -can't you beat that!- when he's old and ailing: his glory days are left behind, but he's still on the top.

... And for the top of these pyramyds he stands, still challenging many a living actor and director, Forty years after his death.

Well, you are welcome to join the gang: Laughtonians of the world, Unite!