Ninety years ago, on November 4th, a week before the armistice, Private George Swain was wounded in the head on the Western front, and repatriated to England to heal his wound. Some time later, his claim for a war pension was declined, as the examiners considered that he had fully recovered from his injury, and wasn't incapacitated by it. Even though George's claim didn't succeed, I'm glad he tried, because his case was filed among the War Pension files, and that file, unlike his service record (one of the many to dissapear during World War Two as a result of enemy bombing), has survived to our days.

And how relevant, you may wonder, is this for this blog? Well, quite so, for George Swain was a pal of Charles Laughton during the First World War.

By summer 1918, George Swain was serving, as Charles, with the 2/1st battalion of the Huntingdonshire Cyclists (both in D company). Along with Charles and many other boys in that Battalion, he was drafted to reinforce other units in France. By the earliest regimental number mentioned in his War Pension Record, it is quite likely that George, as Charles and John Agar (another boy in D company), received his early training at the 87th Training Reserve Battalion at Catterick. As at least Charles and another two men in that list, Swain was a Yorshireman, which gives you a picture of how manpower was dealt with at this late stages of the war: in its early stages, men were keen to enlist, and serve, in their "county" regiments, but by 1918 such sentimental choices just weren't available to the young conscripts, who were just posted to wherever reinforcements were needed... Thus you could have these Yorkshire boys, going from the (Conscription) Training Reserve Battalions right after being called up, then being posted to a Huntingdonshire regiment (Territorial) to guard the coast of Lincolnshire, and then again. posted (for the records) to the 4th Bedfordshires (a Regular battalion), and then serving at the front in France with the 7th Northamptonshires (a "Kitchener" or New Army battalion)... That's running the whole gamut, if you ask me.

A bit of background: Desperately Seeking Charles' War Record

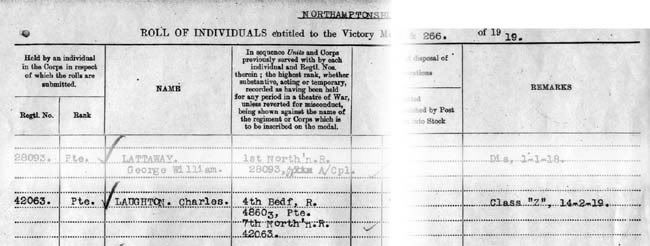

Charles' Medal card...

...And Charles' entry in the Medal records, which fortunately mentioned the battalions of the regiments he was allocated to, except the Huntingdonshire Cyclists, sadly not mentioned

When, years ago, I went to London to -among other things- try to find Charles' war record, I found out that it wasn't among those which survived the World War Two bombings. While I knew that this was likely, I couldn't help feeling dissapointed. But along with disappointment came an idea... What would came if I checked medal records for people with numbers correlative to Charles'? As I checked some 100 numbers over and under Charles' in the two regiments mentioned in his Campaign Medals card, I found out there was a pattern... Could these men whose numbers and regiments were coincident with Charles' have served in the same battalions together?

The answer was yes. And this was confirmed when Mr. Martyn Smith (the Huntingdonshire Cyclists' dedicated historian, and keeper of the afore-linked -and excellent- website on them) most kindly sent me copies of some of the surviving Battalion Orders of the 2/1st Huntingdonshire Cyclists, where, among other things, Charles was mentioned, along with other boys, as part of a draft being sent to the front on August 9th, 1918 (that list is also afore-linked). This was quite the Rossetta Stone of our research, as it provided both the confirmation of Laughton having been at the Huntingdonshire Cyclists (so far we had only an old picture with his badge, plus vague mentions of it in biographies), and also the date when he was drafted to France. With this information on our hands, we proceeded to elaborate a webpage containing what we knew so far about Charles' Great War service (with some related links for context, etc.). There were, of course, many questions remanining... I later found mention by Charles, scattered in old interviews, about his serving with the 7th Northamptonshires during the war, which further confirmed the medal card data, along with a few excerpts from an exchange of letters with an old comrade from the battalion.

Still, many questions remained... When did Charles reach the frontline? What about the 4th Bedfordshires? When was he gassed? etc, etc...

Two relevant pages of George Swain's pension record.

At least one of these questions was answered when Mr. Stephen Beeby, a dedicated Great War researcher from Cambridgeshire, reached me with excellent news. He had found George Swain's Pension record, which mentioned George's itineraire through units during his war service... Of course there must be divergences with Charles' service, among them the fact that George's scalp wound caused him to be repatriated to England, while Charles, as a gas casualty, quite surely had to heal on a French hospital after receiving first aid. It is interesting that the War Diary of the 73rd Ambulance (WO 95/2202), caring for the wounded men of the 73rd Brigade (24th Division, Third Army), to which the 7th Northamptonshires belonged, contains a diagram of how to build a centre to deal with gas casualties, which helps to picture how Charles may have received his early treatment (You can see a better-resolution image, plus more related details here

How the 73rd ambulance organized a centre to deal with gas cases of every type (WO 95/2202. National Archives. Crown Copyright).

The Last Hundred days

Knowing already the date when Charles left England, Thanks to George Swain's War Pension record, we also know that the draft of Huntingdonshire Cyclists disembarked in France on August 10th, 1918, then was "posted to 4th battalion for records"... which clears the 4th Bedfordshire question, as this reveals that those boys were there just for administrative reasons, not even changing their regimental numbers in the process. In fact, on August 12th, they are definitely allocated -and given new regimental numbers- to the 7th Battalion, Northamptonshire Regiment. Thus Charles and Co. were 4th Bedfords for just a couple of days, and just for the records.

The draft seems to have spent little time in "transit" camps in the coast, like the well-known, and enormous, Etaples camp, instead, they were sorted quite quickly to the 24th Division's reinforcements' camp, just eight days after landing in France, where one imagines them getting an extra bit of training to prepare them for front-line action, and by the September 8th, the draft finally joins the 7th Northamptonshires. As you can see in the battalion's diary here, those days were spent in training and reorganization at Marqueffles Farm (not far from Lens), plus accomodating the newly arrived (sadly, the arrival of the new draft is not even mentioned in the diary: one regrets that the officer in charge of the diary was not too exhaustive in his recording of the facts).

Incidentally, all this is rather consistent with Elsa Lanchester's statement, in her 1938 biography "Charles Laughton and I" of Charles being sent "straight to the front", and therefore, it is likely that the mention of Charles being gassed "one week before the war" is accurate as well, and not just a foggy "family tradition". Among other things, because it was on the November 4th when George Swain was wounded, in the course of a battle in which the 7th Northants were involved, but we'll come back to that later.

Charles' draft reached the Battalion in time to take part in the campaign that has become known as The Last Hundred Days, in which, after the Battle of Amiens, the allies advanced steadily, at a pace which spectacularly outspeeded the gains of battles in previous years. The daily casualty rate of the British was higher than those of either the Battle of the Somme or Third Battle of Ypres (Passchendaele), if not as high as that of the Battle of Arras.

During those days, the 7th Northamptonshires held the line and were involved in actions such as the battles of the Hindemburg Line (September 12th to October 9th, 1918), The Battle of Cambrai of 1918 (October 8th and 9th), the Pursuit to the Selle (October 9th to 12th), and then in the final advance through Picardy, in the Battle of the Sambre. It was in the course of this action that George Swain was wounded (and quite likely Charles, too).

November 4th, 1918: The Battle of the Sambre starts

The day when the Battle of the Sambre started there was a thick groud mist, which, according to J.P. Harris, in his book "Amiens To The Armistice" (1998) was a fact which "tended to reduce casualties from machine-gun and rifle fire", by dusk, the XVII Corps (to which the 7th northants belonged), had taken all the planned objectives for the day, making an advance of 3 to 4 miles. You can get a helpful bird's view of the action from the Diary (WO 95/2217) of the 73rd brigade, (which comprised the 7th Bn. Northamptonshire Regiment, the 9th Bn. Royal Sussex Regiment and the 13th Bn. Middlesex Regiment) by clicking here and see a map of the battle by clicking here.

As far as the the ground view of events is concerned, here we have the account of these days the from the 7th Northamptonshires' War Diary:

November 4th 1918. Bermerain

B and D Companies were detailed as support to the 9th Bn Royal Sussex Regiment (73rd Brigade, 24th Division) who were to attack along the whole Brigade front from a line which had been established West of the Enlain-Villers Pol Road. Capt. A. Elliman was in command of D Company and supported right flank and Capt. B. Wright the left flank. These two Companies moved off at 3 am, crossed the river Rhonelle by bridges which had been put into position by A Company the night previous, and took their position by early morning. A and C companies remained in the positions occupied the previous night until 6 am and then moved to the rear of the general line of advance. The barrage commenced at 6 am and the Companies moved forward. D Company was caught in the Hun counter-barrage and a number of casualties were caused. The remainder were led onward and in time formed part of the front line. By 8 am they were on the high ground in front of Wargniers-le-Petit. Capt A. Elliman and 2/Lieut J. W. Tetley had both become casualties (wounded). B Company successfully eluded the counter-barrage on the left (N) flank and succeeded in establishing themselves in a position which dominated the small bridge over the river Aunelle. This bridge carried the main Enlain-Bavay Road which separated Wargniers-le-Grand and Wargniers-le-Petit and by concentrated Lewis Gun and rifle fire and by forward patrols they managed to keep it whole. The enemy was shelling the sunken roads and were sweeping the ridge with machine gun fire. The position, having become stationary, it was decided to relieve the pressure by outflanking both villages from the north. The 13th Bn Middlesex Regiment (73rd Brigade, 24th Division) was allotted Wargniers-le-Grand and the 7th Northamptonshire Regiment, Wargniers-le-Petit.

14.30 hours- A and C Companies were detailed for this duty. They were to cross by keeping their left on the main road and push through the village and then onward to the high ground East of it. C Company formed the front line under 2/Lieut. C. Pike and A Company under Capt. G. A. Williamson were in support. Machine gun fire was met with but overcome by grenades and rifle fire and both Companies established themselves well forward of the village. B Company now became support and D Company having been withdrawn from the front line went into reserve. The enemy began to shell the outskirts and roads leading to the villages which were inhabited by a fair number of French civilians. 50 prisoners were taken during operations.

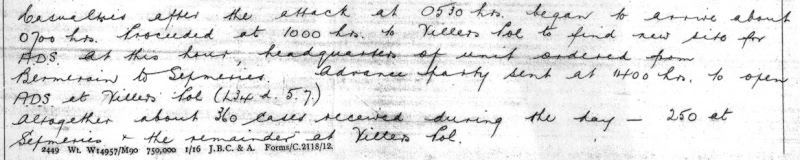

Again, we don't get here a comprehensive picture, apart from the officers (mentioned by name) the casualties from the ranks are just given as an anonymous "number of casualties" in D Company. Since we know that George Swain pertained to B Company, it is undoubted that D company was not the only part of the battalion to suffer "a number of casualties", in fact, if we peer at the 73rd Ambulance's diary, we see the casualties for the three battalions and other divisional units amounted to 360 cases, roughly a tenth of the men involved (and that in the case that the battalions were at full establishment, and they were most probably not so, due to prior casualties duirng days of sustained fighting)

73rd ambulance's entry for November 4th(WO 95/2202. National Archives. Crown Copyright)

So here we have one more piece in the puzzle of Charles' war whereabouts. As the song says, who knows what the future holds, so I don't discard further little details coming up, each one a little miracle. One may debate about whether the gods exist or not, but miracles do happen!

This post is respectfully dedicated to those soldiers who, like Charles, were serving on November 11th, 1918, Saint Martin's day.

Bibliography

Apart from the already mentioned diaries, plus the books mentioned in the pages containing the known information, J. P. Harris' "From Amiens To The Armistice" (Brassey's, London 1998) has been a most helpful information resource about late 1918 events in the Western Front.

Acknowledgements

I'm deeply grateful to Mr. Stephen Beeby, who recently brought to my attention George Swain's record, and also to Mr. Martyn Smith, for all the continued help through the years relating the Huntingdonshire Cyclists